The 1970s were a great decade for science fiction. There

many great books ranging from hard SF stories about ringed planets and

self-contained ecosystems in space craft to soft SF stories of cloning and

individuality and genderless societies to stranger tales of resurrected people

living on the banks of an endless river and three gendered aliens. It was the

first decade a woman, Ursula Le Guinn, won the Hugo Award. In fact, four out of

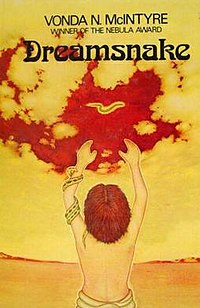

the ten 1970s winner were written by women including 1979’s Dreamsnake by Vonda N. McIntyre. In a

decade of great highs, Dreamsnake holds its own but does not reach the heights

of such classics as The Left Hand of

Darkness, The Forever War, and Gateway.

Dreamsnake

takes place far in the future after a nuclear war has rendered vast swaths of

the landscape radioactive. Yet it is not a desolate world with small groups

struggling to survive. Society has reformed and the old world is mentioned only

in passing. I love how McIntyre implies years of history to the world without

giving too much detail. Like the

Hechee in Gateway, the reader is only

able to guess and infer what has happened. For example, title creature is from

another planet but the reader is never told what planet, why they came to Earth

or how brought them there. Further on that point, the main character goes to a

city that still trades with aliens but she is unable to get in and we the

readers never learn anything about the aliens and very little about the closed

city that trades with them. It’s a nice mystery that enhances rather than

detracts from the story.

The

story itself is about a healer named Snake who uses three snakes; a

rattlesnake, a cobra, and the eponymous dreamsnake, and her trails to replace

the dreamsnake after a misunderstanding with some tribespeople led to its death.

Snake’s journey is not straight path since she does not know quite how to replace

the rare dreamsnake and is loath to return to the healers and admit her

failure. She travels through the land, helping people as she can with her two remaining

snakes, picks up a companion, and ultimately succeeds in her goal. While that

may seem like a spoiler but how Snake accomplishes it a bit surprising but felt

completely organic and not contrived.

It might

sound strange how snakes are used for healing but McIntyre explanation is

original. The snakes are specially bred to metabolize medicines within their

systems. Snake feeds the rattlesnake or the cobra a compound that turns their venom

into whatever medicine she needs and the repurposed venom attacks the illness

with the same ferocity that it would have as a poison. She uses the snakes to

transmit vaccines to nomads and kill a nasty infection in a wounded leg. The

dreamsnake’s purpose is different, however. The dreamsnake takes away the pain

and calms people. It can be used to calm a person who is undergoing surgery or

suffering from an illness or ease the passing of a dying individual. Without,

Snake feels she cannot do her job sufficiently. It is an interesting and well

realized idea that helps to show this future world as both similar to our

current world but alien as well. While much of the world is less advanced that

our world, for example people use horses instead of motor vehicles and some

live nomadic lives, in some ways it is more advanced. The snakes are shown to

be more effective that modern medicine and people are able to control their own

biological functions to such a degree that unwanted pregnancy is virtually

unknown. It is a great world and I do wish that McIntyre had created more

stories within it.

There

is really not much else to say. Dreamsnake is a thoroughly enjoyable science

fiction tale that entertained me but did not leave the lasting impression that

some of the greatest works did. I am find with this. When I started this

strange project a few years back, I did not expect every work to be great but I

did hope that every work would be good. What is important is that Dreamsnake

was good and I am glad this little project brought it to my attention.

My next

blog will be summary of my impressions of the 1970s as I did with the 1950s and

the 1960s. After that it is one of the three “Greats” of science fiction:

Arthur C. Clarke and his 1980 novel, The Foundations of Paradise. Happy reading

until then!